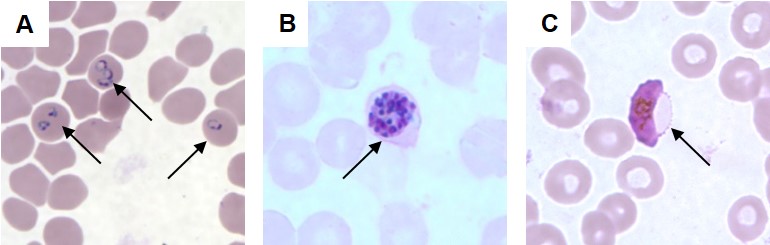

Figure 2: Example of blood film

being

taken to test for malaria

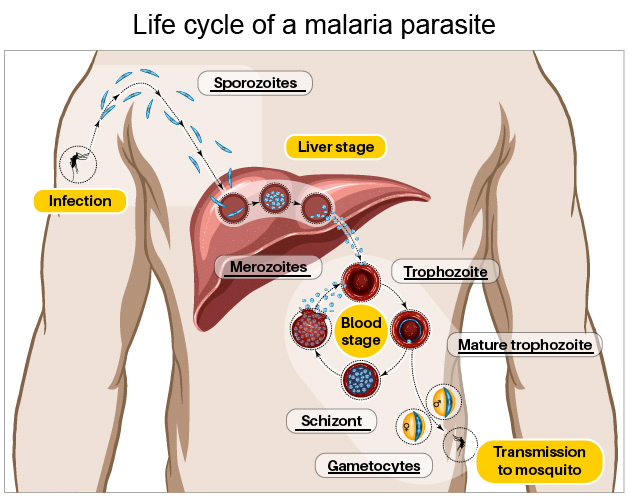

While malaria is frequently associated as a disease caused by mosquitos, female Anopheles mosquitos are merely extremely competent vectors of the Plasmodium parasite, the true perpetrator of this disease. There are five species of this unicellular protozoan parasite (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. knowlesi and P. malariae) that cause malaria in humans. P. falciparum, however, is the most infectious and responsible for severe forms of the disease. When a mosquito bites a person infected with malaria, the parasite is taken up together with its blood meal. The next time the mosquito bites a human, these parasites are injected into the unfortunate victim together with the mosquito's saliva (Fig. 3).

Once infected, malaria symptoms typically emerge anywhere from 10 days to a month, and are manifested in the form of fever, chills, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and other flu-like symptoms. As an infected person's red blood cell count decreases, an effect of the disease, they might become anemic and jaundiced. If the infection remains untreated and continues to advance, it may result in seizures, mental confusion, kidney failure, coma, and even death. People with lowered immunity, such as pregnant women, children, infants, and travelers from countries with no previous exposure to malaria, are particularly susceptible to this disease.

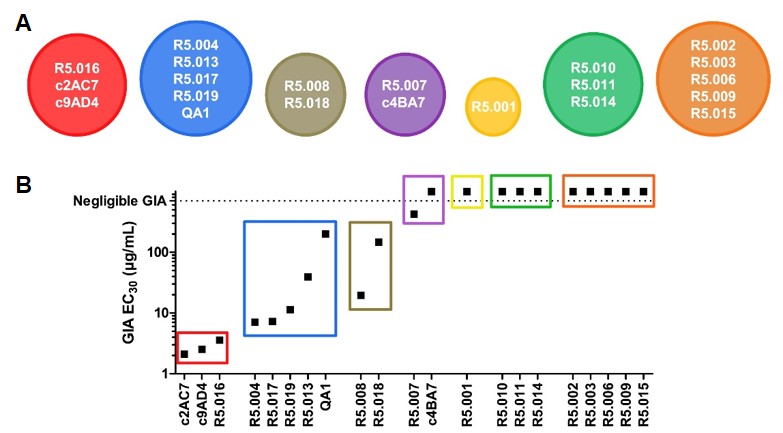

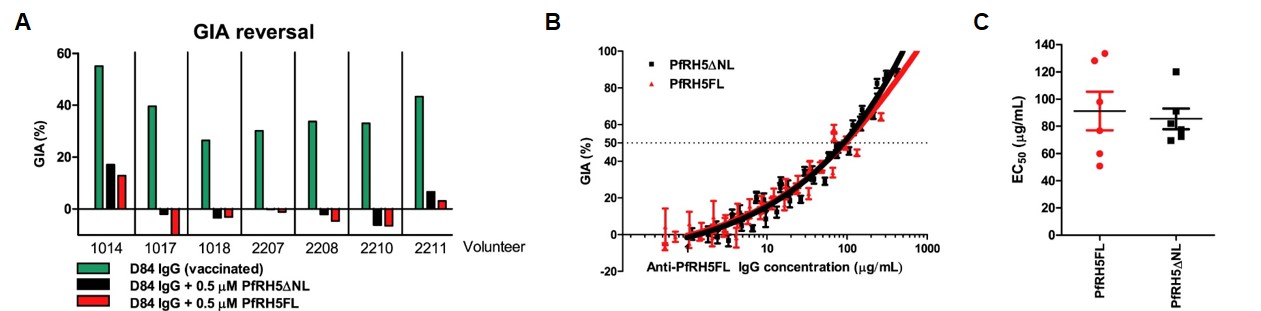

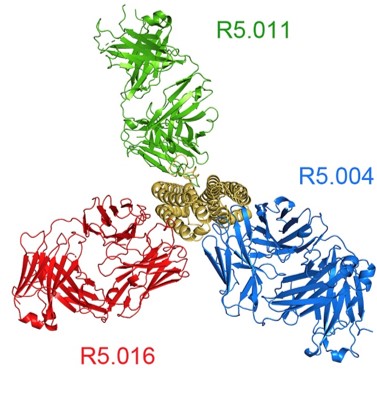

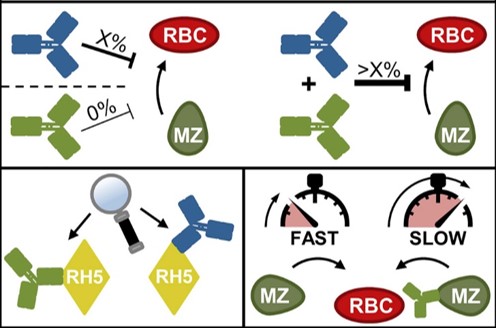

Malarial vaccines have been in development for the

past 50 years with still no licensed product

confirmed to date. Today, there are quite a number

of malarial vaccine candidates in clinical

development, including the blood stage PfRH5-based

vaccine described in the study above. In addition to

RTS,S and the PfRH5-based vaccine described above,

Sanaria ® also has a vaccine developed

based on the whole P. falciparum sporozoite

that has been irradiated to render it

non-infectious. Ongoing studies in Western Kenya

show that the Sanaria® vaccine appears to

be safe, well-tolerated, and confers protection

against malaria.

Malarial vaccines have been in development for the

past 50 years with still no licensed product

confirmed to date. Today, there are quite a number

of malarial vaccine candidates in clinical

development, including the blood stage PfRH5-based

vaccine described in the study above. In addition to

RTS,S and the PfRH5-based vaccine described above,

Sanaria ® also has a vaccine developed

based on the whole P. falciparum sporozoite

that has been irradiated to render it

non-infectious. Ongoing studies in Western Kenya

show that the Sanaria® vaccine appears to

be safe, well-tolerated, and confers protection

against malaria.